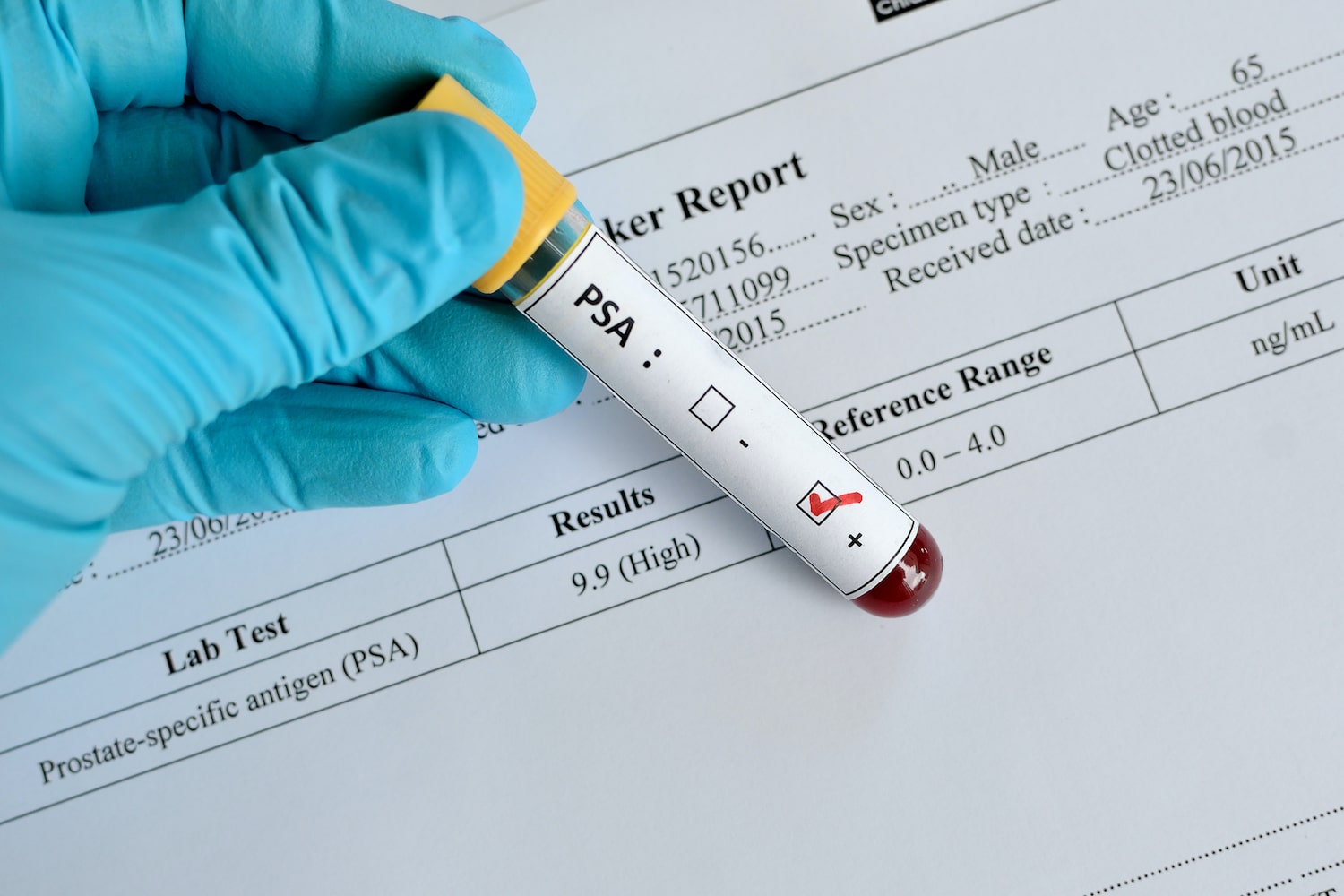

News that former U.S. President Joseph Biden has advanced prostate cancer has reignited long-standing debate over the merits and drawbacks of the PSA (prostate-specific antigen) blood test, used to screen for the most common cancer in American men.

While the PSA test can detect cancer, many doctors and public health experts say it’s a blunt instrument—unable to consistently distinguish between aggressive tumors like Biden’s and slow-growing ones unlikely to pose a threat. Autopsy studies reveal that over one-third of white men and half of Black men in their 70s have undetected prostate cancers that would likely never become dangerous.

Radiation oncologist Dr. Brent Rose, of UC San Diego, notes that “PSA testing alone leaves a lot to be desired” due to its potential for false positives, unnecessary biopsies, and overtreatment that can lead to severe side effects such as impotence and incontinence. Still, he says, “PSA screening is beneficial—it’s a personal decision that should involve a careful conversation with one’s doctor.”

A Controversial Screening Tool

The PSA test measures levels of a protein produced by both healthy and cancerous cells in the prostate. Elevated levels can indicate cancer but may also point to non-threatening conditions. That uncertainty has caused physicians to tread carefully since PSA testing became common in the 1990s, especially given its potential for unnecessary interventions.

Doctors like Rose aim to target and treat only high-risk cancers, while observing less dangerous ones through “active surveillance.” But without a superior alternative test available, PSA remains the primary tool for screening the second deadliest cancer among American men.

Guidelines Have Shifted Over Time

Public health guidance on PSA testing has shifted multiple times, creating confusion. In 2012, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) advised against PSA screening altogether. But in 2018, it softened its stance, recommending that men aged 55 to 69 make the decision in consultation with their doctors. For those 70 and older, the task force continues to advise against screening—guidance Biden appeared to follow, as he last had a PSA test in 2014 at age 71 or 72.

The current Grade C recommendation for men in the 55–69 range implies that benefits are small and insurers might not cover the test. Still, many doctors believe this cautious approach complicates meaningful discussion between patients and physicians—especially when time is limited in primary care settings.

Some patients appreciate the opportunity for shared decision-making, while others find the ambiguity stressful. For now, the consensus remains: men should have an informed conversation with their healthcare providers.

Calls for Broader Screening Access

Dr. Alicia Morgans, a medical oncologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, wants updated guidelines. In August, she met with the USPSTF as part of her role at Zero Prostate Cancer, an advocacy organization. Morgans believes the task force relied on flawed data—particularly a study in which 90% of men in the control group had PSA screenings, skewing results.

She supports earlier and more consistent testing, particularly for high-risk groups like Black men and those with a family history of prostate cancer. “I see both ends—patients with curable disease and those with advanced cancer,” she said. “I want to catch it when it’s still curable.”

Dr. Matthew Cooperberg, a urologic oncologist at UC San Francisco, agrees. He advocates for renaming low-grade prostate cancers with terms like “acinar neoplasm,” to reduce fear and avoid overtreatment. He also encourages active surveillance for men with mild abnormalities. “If we reserve treatment for aggressive cases, we can nearly erase this cancer as a lethal disease,” he argues.

A New Screening Era Takes Shape

Not all physicians are as optimistic. Dr. Tyler Seibert, another radiation oncologist at UC San Diego, says the field is moving away from automatic biopsies after a high PSA reading. Instead, he recommends MRIs and a period of watchful waiting to better distinguish which cancers pose real threats.

The initial approach to PSA testing, Seibert says, wrongly assumed that every cancer detected must be treated. Today, doctors know that many of these cases never require intervention. “For men with low-risk prostate cancer, we now have strong evidence that close monitoring is enough,” he explains.

Still, Seibert acknowledges that the idea of living with an untreated cancer can be emotionally taxing. “Every PSA test brings a little anxiety,” he said. “But if you can handle that, screening can absolutely make sense.”

This evolving understanding of prostate cancer and PSA testing is shaping a new, more nuanced approach—one that attempts to save lives without unnecessarily harming those who might never have needed treatment in the first place.