A Common Virus With Uncommon Outcomes

A simple cold can feel like a minor inconvenience for some people and a frightening health crisis for others. This striking contrast has long puzzled scientists, especially when the culprit is rhinovirus, the most frequent cause of the common cold. For Dr. Ellen Foxman, an immunologist at the Yale School of Medicine, the question became deeply personal after witnessing her young son struggle to breathe during a severe asthma attack triggered by what would otherwise be considered a routine infection.

Rhinovirus is remarkably widespread and, in many cases, barely noticeable. Large portions of the population carry the virus with nothing more than mild nasal congestion or no symptoms at all. Yet in people with asthma or other respiratory vulnerabilities, the same virus can provoke intense airway constriction, excessive mucus, and dangerous inflammation. The mystery lies not in the virus itself, but in how the human body reacts once the pathogen enters the nose.

The Nose as the Front Line of Defense

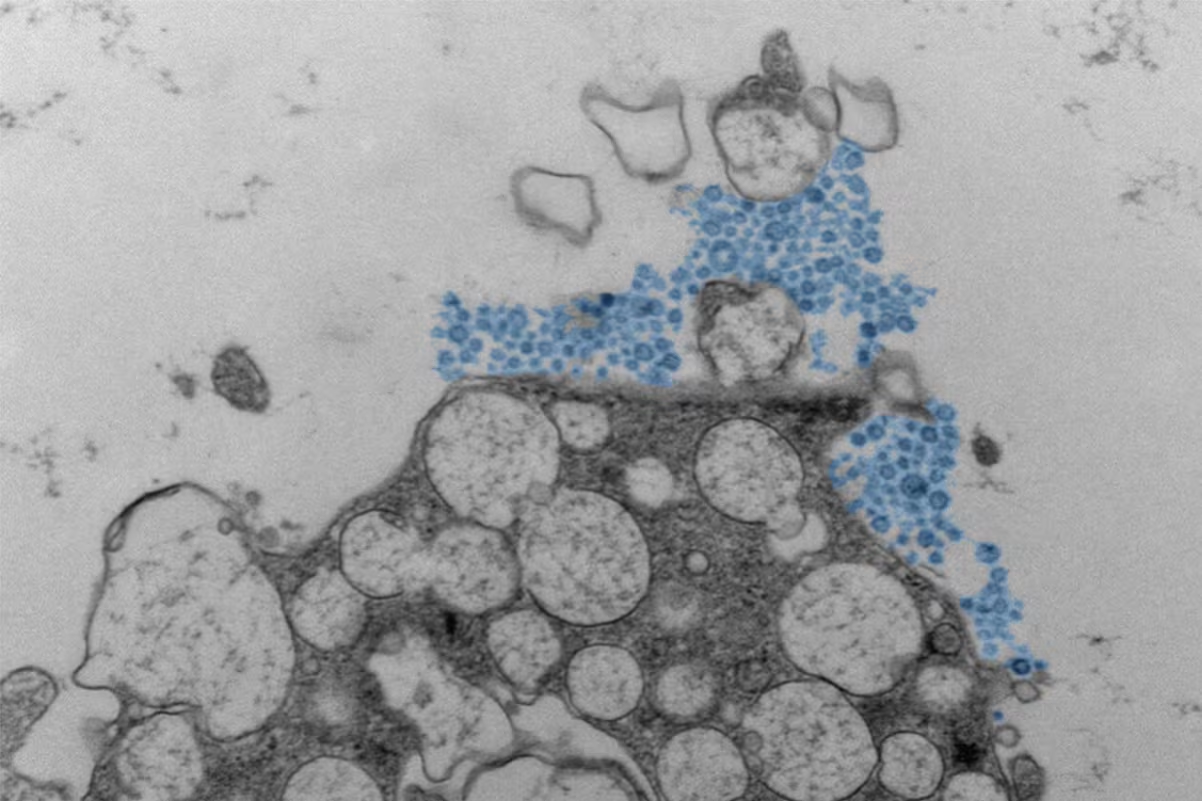

Foxman and her research team focused their attention on nasal epithelial cells, the first cells to encounter rhinovirus. These cells are not passive barriers; they actively coordinate the immune response. Central to this process is the interferon response, a rapid alarm system that helps prevent viruses from spreading deeper into the body. According to immunology frameworks supported by institutions such as the National Institutes of Health, interferons play a crucial role in containing respiratory infections at an early stage.

In laboratory experiments, Foxman’s team cultivated nasal cells from healthy adults and exposed them to rhinovirus under controlled conditions. When interferon signaling activated quickly, the infection remained tightly contained, affecting fewer than 2% of cells. In that scenario, symptoms would likely be limited to a mild cold or go completely unnoticed. However, when researchers artificially blocked this early interferon response, the results changed dramatically: nearly one-third of the cells became infected, accompanied by heavy mucus production and widespread inflammation.

These findings suggest that the severity of a cold is less about viral strength and more about timing. A delayed immune response gives the virus a window to spread, amplifying symptoms and increasing the risk of complications, particularly in people with asthma.

Beyond Interferons: Why Responses Still Vary

The study, published through Cell Press, represents a major step forward in understanding early immune defenses, but it does not provide all the answers. Researchers caution that interferon activity is only one piece of a much larger puzzle. Genetics, existing airway conditions, previous exposure to similar viruses, and even the presence of certain bacteria in the nose may all influence how the body reacts.

Medical experts at institutions like the Emory University School of Medicine emphasize that this variability is not unique to rhinovirus. Similar patterns appear across respiratory illnesses, including influenza and other viral infections, where two people exposed to the same pathogen can experience vastly different outcomes. While boosting interferon responses may one day become a therapeutic strategy, scientists stress that more studies involving real-world patients are needed to understand how these immune mechanisms operate outside the lab.

For now, the research highlights a crucial insight: when it comes to the common cold, the decisive factor is not just the virus you catch, but how swiftly and effectively your immune system responds in those first critical hours.