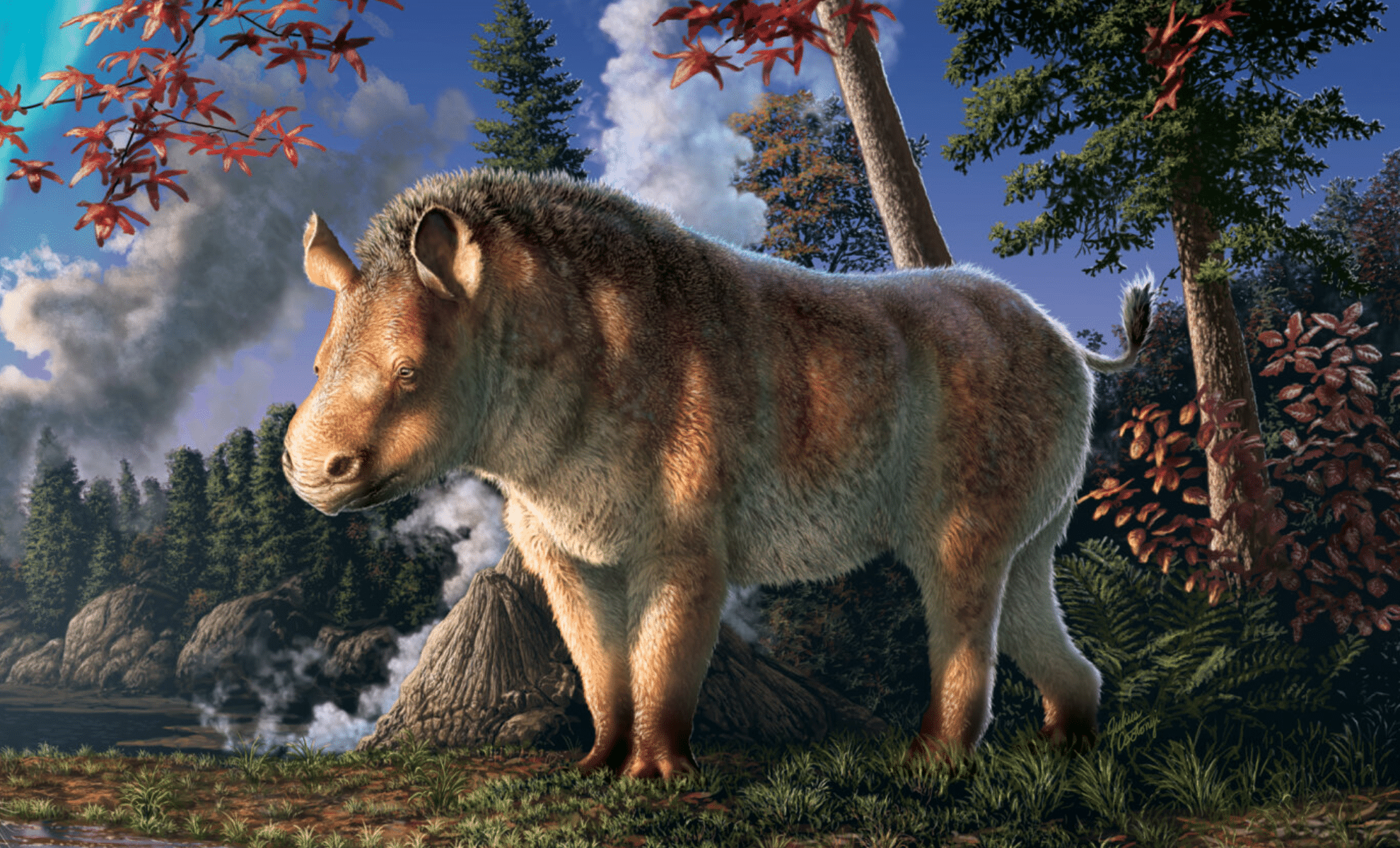

The identification of Epiatheracerium itjilik, a rhinoceros species that lived in the High Arctic around 23 million years ago, is providing researchers with striking evidence that large mammals moved across northern landscapes far later than previously believed. This small, hornless rhino once lived in an Arctic environment that resembled a temperate forest, a setting dramatically different from the frigid conditions present today. The nearly complete skeleton, preserved for millions of years thanks to permafrost, is giving scientists a rare opportunity to reconstruct long-lost evolutionary pathways. As paleontologists continue to investigate this remarkable site, they emphasize how discoveries in extreme regions can transform current understanding of how mammals adapted, moved, and diversified through time. This work also highlights the significance of fossil preservation, especially in areas now vulnerable to rapid environmental change.

The team’s analysis places the species close to rhinos that once inhabited Europe and Western Asia, suggesting that the Arctic provided a passageway enabling the spread of mammals across continents. This revelation implies that migration routes remained open long after researchers had assumed these pathways disappeared beneath the ocean. These findings are now guiding specialists toward more detailed investigations into northern ecosystems, environments that appear to have played a far more influential role in global biodiversity than traditionally acknowledged. For readers interested in broader prehistoric contexts, additional background on Earth’s changing environments can be found at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (https://naturalhistory.si.edu), a resource frequently used by researchers worldwide.

Revisiting the North Atlantic Land Bridge and Its Role in Mammal Dispersal

For decades, the Bering Land Bridge dominated narratives about ancient animal movement, yet this new discovery is shifting attention to the North Atlantic Land Bridge. Scientists had long believed that the landmass connecting Europe and North America disappeared beneath rising seas around 50 million years ago. The presence of Epiatheracerium itjilik in the Arctic, however, indicates that rhinos were still using this corridor at least 20 million years later. This extension dramatically changes the timeframe during which mammals traversed northern continents and suggests that climate conditions remained suitable for movement and survival for a much longer period.

The rhino’s skeleton shows strong similarities to European and Western Asian species, supporting the idea of two-way movement across the northern passage. These connections raise new questions about how environmental changes influenced long-distance dispersal and how mammals adapted to seasonal darkness and cooler temperatures. The American Museum of Natural History (https://www.amnh.org) provides helpful overviews of land bridges and evolutionary transitions, offering context for readers interested in how such pathways shape global biodiversity.

From an evolutionary perspective, the Arctic seems to have acted as a biological gateway rather than a boundary. This interpretation positions the region as a key driver in shaping the diversity of mammals, challenging assumptions that warm tropical areas were the primary sites of evolutionary innovation. The emerging evidence shows that northern ecosystems played an essential, long-lasting role in shaping the distribution and evolution of prehistoric species.

Ancient Proteins and the Growing Importance of Arctic Fossil Sites

One of the most remarkable aspects of the study is the recovery of ancient proteins dating back roughly 21 million years. These biomolecules, found within the enamel of the rhino’s tooth, provide one of the oldest molecular records ever sequenced. Their durability allows researchers to explore evolutionary relationships in ways that DNA cannot, particularly for species that lived in deep time. Ancient proteins are enabling scientists to ask broader questions about mammal origins, biogeography, and diversification, expanding the possibilities for reconstructing early evolutionary history.

The preservation of these proteins was only possible because of the extreme cold conditions in the Arctic. As warming temperatures cause ice loss and erosion, researchers fear that sites rich in fossils and biomolecules may be damaged or destroyed. This growing concern is prompting scientists to accelerate fieldwork and develop new strategies to study vulnerable areas before they change irreversibly. For readers interested in current research on climate effects in polar regions, the National Snow and Ice Data Center (https://nsidc.org) offers continuously updated insights into environmental shifts.

Collaboration with Indigenous communities played a meaningful role in naming the new species and guiding research in the surrounding region. Working closely with Inuit leaders has helped improve cultural understanding, strengthen field research, and inspire local youth to participate in scientific exploration. This approach reflects a growing movement toward inclusive research practices that respect the knowledge of the people who live in and understand these landscapes. For additional perspectives on Indigenous-led conservation and cultural stewardship, the website of Parks Canada (https://parks.canada.ca) provides extensive information on northern heritage, protected areas, and community involvement in scientific projects.

As discoveries like Epiatheracerium itjilik continue to emerge, they reaffirm the importance of Arctic paleontology in reconstructing ancient life and tracing the routes that once connected continents. Each fossil, protein fragment, and collaborative effort expands the understanding of how mammals adapted to shifting climates and how northern ecosystems once shaped the world’s biodiversity.