Mentioning Donald Trump’s name in the halls of wholesale markets or trade fairs in China often provokes discreet laughter. The U.S. president and his 145% tariffs have not sparked fear among many Chinese merchants. On the contrary, they have triggered a wave of satirical content on social media, with viral videos featuring AI-generated figures—like Trump, Vice President JD Vance, or Elon Musk—manufacturing shoes or assembling iPhones.

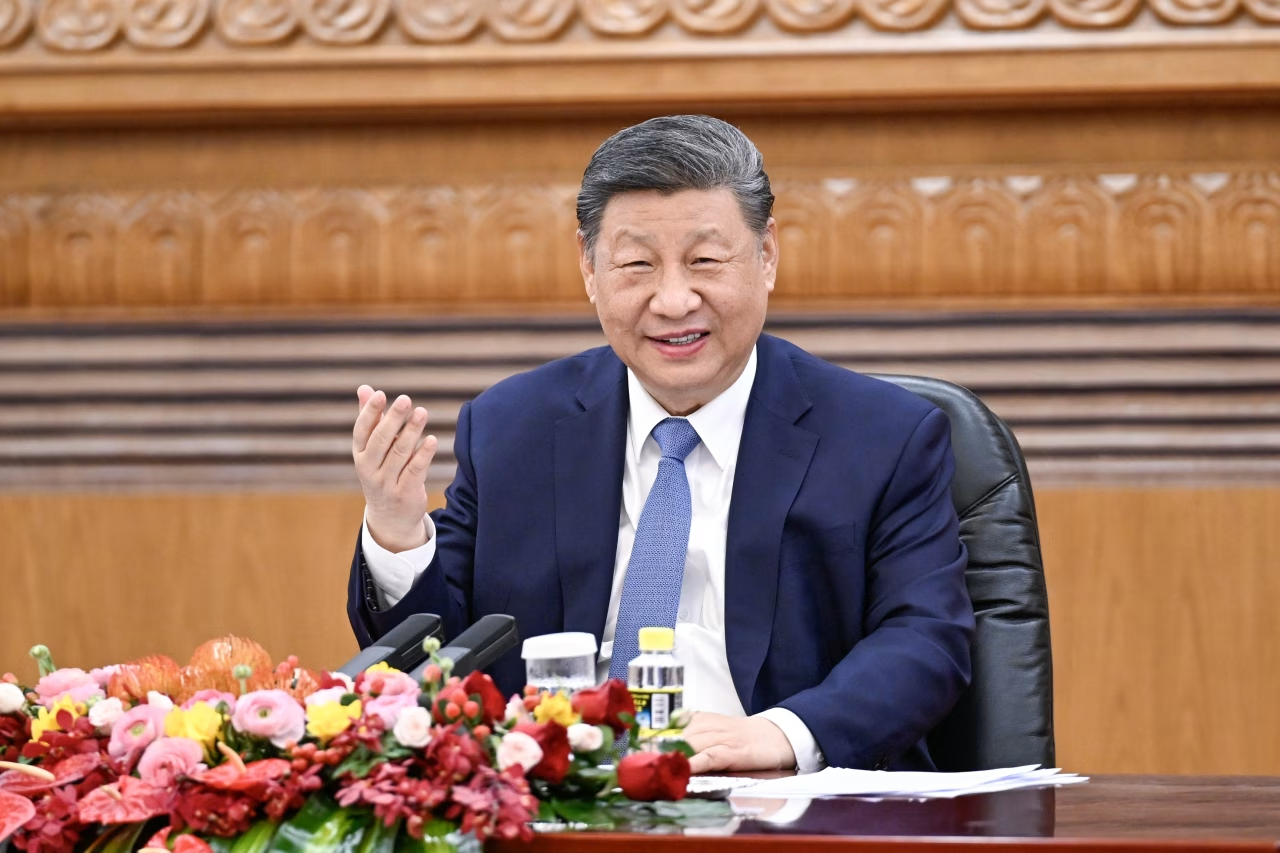

China is not acting like a country facing imminent economic damage, and President Xi Jinping has made it clear that Beijing will not yield to pressure. “For more than 70 years, China has relied on its own efforts to develop… it has never depended on others’ gifts and does not fear unjust pressure,” he recently declared.

Part of that confidence stems from the fact that China depends less on exports to the U.S. than it did a decade ago. However, Trump’s measures are pressing on sensitive points in a Chinese economy already facing internal tensions: a real estate crisis, job insecurity, and population aging. These factors have reduced domestic consumption, something the Chinese government is trying to reverse.

Xi came to power in 2012 with a vision of a renewed China. Today, that ambition faces serious tests that go beyond tariffs. The question is whether U.S. policies will frustrate Xi’s plans or whether Beijing will manage to turn challenges into opportunities.

Internal Challenges for Xi

With 1.4 billion inhabitants, China has a large internal market. But the problem is that consumers are not spending, due to economic uncertainty. This is not due to the trade war, but to the collapse of the real estate sector, where many families invested their savings and have seen prices plummet over five years.

Developers kept building despite the crisis, and it’s estimated that the country has enough empty housing to accommodate 3 billion people, according to He Keng, former deputy director of the National Bureau of Statistics. Touring some provinces reveals ghost developments: completed structures, with gardens and curtains, but no lights at night—evidence that they are uninhabited.

Five years ago, the government imposed borrowing limits on developers, but the damage had already been done. Reuters projected a 2.5% drop in housing prices for this year. Added to this is the concern of many families about whether they’ll be able to access a pension. In the next 10 years, about 300 million workers—aged 50 to 60—will retire. According to a 2019 report from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the state pension fund could be depleted by 2035.

Youth unemployment is also a concern. In August 2023, more than 20% of young people aged 16 to 24 in urban areas were unemployed, according to official figures. Since then, the government has not published new statistics for this group. The problem is that China cannot change its economic model overnight, shifting from foreign sales to relying on internal consumption.

“Internal spending cannot expand significantly in the short term due to economic pressure,” says Professor Nie Huihua of Renmin University.

“Replacing exports with domestic demand will take time.”

Zhao Minghao, deputy director of the Center for American Studies at Fudan University, points out that “China does not have high expectations about talks with the Trump administration… The real battlefield is the adjustment of internal policies to stimulate consumption.”

The government has announced subsidies for childcare, wage increases, better paid leave, and a $41 billion program to encourage purchases of electronics and electric vehicles. However, for Zhang Jun, dean of Economics at Fudan, these measures are not enough:

“We need a sustainable mechanism. Citizens’ disposable income must be increased.”

This situation is crucial for Xi, whose promise of prosperity has yet to materialize after 13 years in power.

A Political Test for Xi

Xi also faces discontent among youth worried about their future, which could pose a political challenge for the Communist Party. A report by China Dissent Monitor, from Freedom House, notes a sharp increase in protests motivated by financial issues.

Although protests are quickly censored and controlled, they do not pose an immediate threat to Xi. “Only if the country prospers will everyone prosper,” he said in 2012. Back then, China’s economic rise seemed unstoppable; now, not so much.

China has made progress in sectors like consumer electronics, batteries, electric vehicles, and artificial intelligence, in its shift toward advanced manufacturing. It has competed with the U.S. in technology, with products like the DeepSeek chatbot and BYD, which surpassed Tesla as the world’s largest electric car maker.

However, Trump’s tariffs could hinder that progress. Restrictions on the sale of key chips to China—including recent measures against Nvidia—aim to curb Xi’s tech ambitions. Despite that, Chinese leadership believes its industry holds structural advantages the U.S. cannot match in terms of infrastructure and skilled labor.

Turning Crisis Into Opportunity

Xi is trying to turn the situation into an opportunity for reform and expansion into new markets.

“In the short term, some exporters will suffer,” says Zhang.

“But Chinese companies are already adjusting their export destinations and looking for new clients.”

Trump’s first presidency pushed China to diversify trade ties toward Asia, Latin America, and Africa. The Belt and Road Initiative strengthened its links with the so-called Global South.

That shift is already bearing fruit: more than 145 countries now trade more with China than with the U.S., according to the Lowy Institute. In 2001, only 30 countries favored Beijing over Washington.

Geopolitical Gains

As Trump applies tariff policies even on allies, some believe Xi can project himself as a stable partner and global alternative in trade leadership. After the tariff announcements, he chose Southeast Asia for his first trip abroad—a gesture toward neighbors.

Today, nearly 25% of Chinese exports are produced or shipped from third countries such as Vietnam or Cambodia. The recent U.S. decisions could offer China a diplomatic opportunity.

“Trump’s coercive tariff policy is an opportunity for Chinese diplomacy,” Zhang points out.

But it must be handled cautiously: some countries fear that products diverted from the U.S. may flood their markets.

In 2016, U.S. tariffs led to a glut of Chinese goods in Asia, affecting local manufacturers. Huihua warns:

“If 20% of China’s U.S.-bound exports are redirected to a single market, dumping and new trade conflicts may occur.”

China has also imposed its own restrictions. In 2020, after Australia requested an investigation into the origin of COVID, Beijing imposed tariffs on wine and barley, and restrictions on meat, cotton, coal, and lobsters. Some exports fell to near zero.

This record could hinder its projection as a defender of free trade. Even so, Xi bets that China will withstand economic pressure longer than the U.S.

And he might be right: last week, Trump hinted at a possible partial reversal of his tariffs, indicating they “will be substantially reduced, but not to zero.”

Meanwhile, Chinese social media is celebrating. “Trump backed down,” was one of the most shared phrases on Weibo after that comment.

Even if negotiations resume, China has a long-term strategy. The previous trade war pushed it to diversify its market; this new stage forces it to look inward and address internal weaknesses. And that will depend on decisions made in Beijing, not in Washington.