Parkinson’s disease is widely associated with tremors and difficulty walking, but for many patients the condition extends far beyond visible motor symptoms. Sleep disturbances, digestive problems, changes in mood, and lapses in thinking are all common features of <a href="/es/”https://www.parkinson.org”/">Parkinson’s disease</a>. Scientists increasingly believe these diverse symptoms share a common cause: disrupted communication within a large-scale brain network that links movement, cognition, and involuntary bodily functions.

Rather than damaging a single brain region, the disease appears to interfere with how multiple areas exchange information. Researchers describe this disruption as a kind of internal traffic jam, where signals struggle to move efficiently between systems responsible for action, emotion, and internal regulation. This perspective helps explain why symptoms can fluctuate dramatically, sometimes improving under pressure and worsening during routine tasks.

A Network That Connects Body and Mind

For decades, neurologists struggled to explain why people with Parkinson’s might freeze while walking yet move suddenly in an emergency, or why talking can make movement more difficult. These inconsistencies hinted that the disorder involved more than motor circuits alone. Advances in brain imaging, including large-scale analyses of <a href="/es/”https://www.nih.gov”/">functional MRI data</a>, have revealed a previously underappreciated network that integrates physical movement with cognitive and emotional processing.

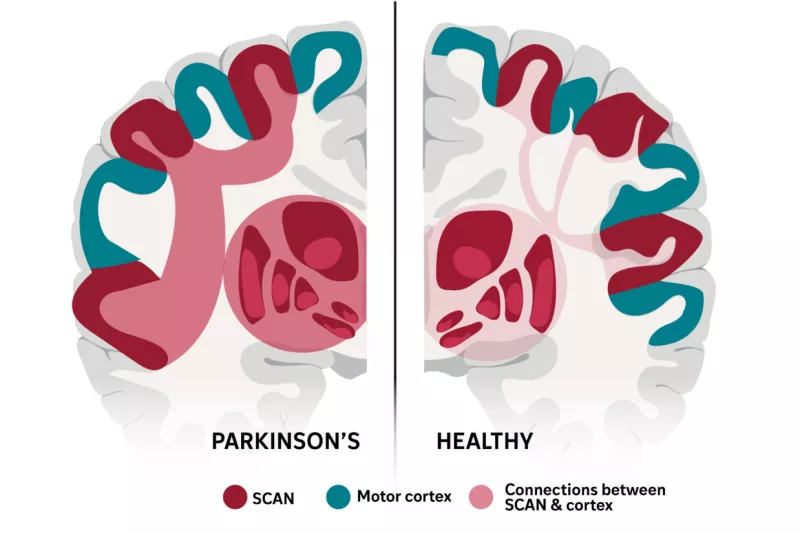

This network links regions involved in planning actions with those that regulate attention, motivation, heart rate, digestion, and sleep. In Parkinson’s patients, connections within this system become unusually strong in the wrong places, disrupting normal signal flow. Instead of improving coordination, the excessive connectivity appears to block efficient communication, leading to the mix of motor and non-motor symptoms that define the disease.

The network-based view also helps clarify why Parkinson’s can affect memory, sense of smell, and blood pressure—functions traditionally considered separate from voluntary movement. When the shared circuitry is impaired, multiple systems are affected at once, producing symptoms that may seem unrelated on the surface but are deeply connected in the brain.

Treatments and the Path Forward

Understanding Parkinson’s as a network disorder reshapes how existing therapies are viewed. Treatments such as <a href="/es/”https://www.fda.gov”/">deep brain stimulation</a>, medication, and noninvasive stimulation techniques all appear to influence the same underlying circuitry. When stimulation devices are activated, abnormal connectivity within the network decreases, allowing signals to move more freely and symptoms to ease.

Importantly, this effect is not limited to one therapy. Different treatments, despite acting in distinct ways, converge on restoring balance within the same brain system. This may explain why certain approaches improve movement while also affecting sleep or mood, even if indirectly.

Researchers believe that targeting overlooked regions within this network could lead to future therapies that address symptoms current treatments fail to resolve. Insights from <a href="/es/”https://www.nature.com”/">recent neuroscience research</a> suggest that focusing on communication between systems, rather than isolated brain areas, may open new avenues for managing both the visible and hidden effects of Parkinson’s.