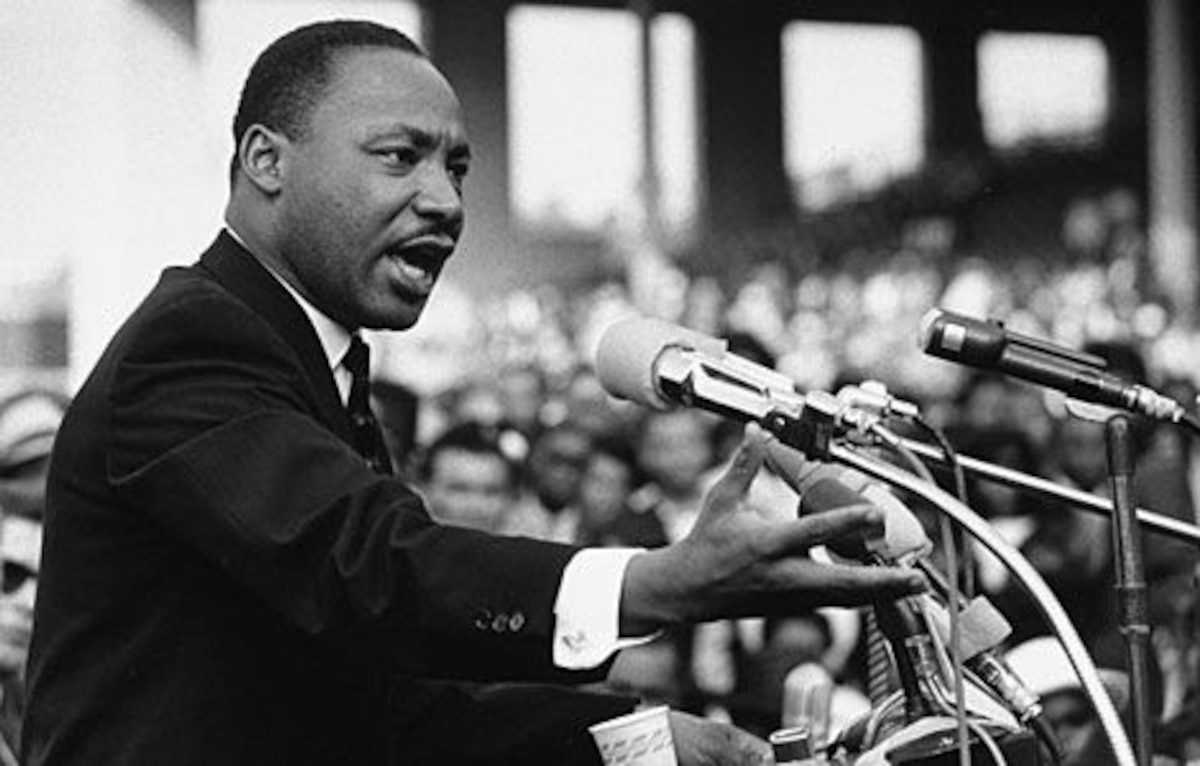

Martin Luther King Jr. is most often remembered for his moral leadership in the struggle for civil rights, yet his ideas extended far beyond voting rights and desegregation. King believed that justice was inseparable from health and dignity, famously stating that injustice in health is among the most inhuman forms of inequality. Decades later, that conviction continues to shape global debates on access to care, prevention, and the responsibility of governments to protect human life. Across low- and middle-income countries, health care injustice remains a defining challenge that mirrors many of the inequalities King fought against during his lifetime.

Exposure to the writings and legacy of African American leaders has inspired generations far beyond the United States. For many young readers growing up in Africa during the late twentieth century, magazines and books became a bridge to understanding leadership, service, and the meaning of justice. King’s words resonated not as abstract ideals, but as practical calls to action. They forced a deeper examination of how health systems function, who they serve, and who they leave behind when prevention fails and care arrives too late.

Primary Health Care as the Foundation of Justice

Health care justice begins at the community level. Preventive and primary health care are often the most effective and affordable tools for reducing avoidable deaths, yet they are frequently underfunded. The concept of strong primary health care was globally endorsed when governments committed to making community-based services the foundation of “Health for All.” Today, institutions such as the World Health Organization continue to emphasize that accessible local care reduces long-term costs and improves population health outcomes, particularly in rural and underserved areas (https://www.who.int).

Countries that invest in community-centered systems demonstrate how equity can be translated into measurable progress. Rwanda, for example, has built a nationwide network of more than 50,000 community health workers who provide early diagnosis and treatment for common illnesses such as malaria, pneumonia, and diarrhea. This model reduces delays that can turn treatable conditions into fatal emergencies. Similar approaches are increasingly supported by development partners and policy frameworks outlined by the World Bank, which links health system resilience to economic stability and long-term growth (https://www.worldbank.org).

The lesson is clear: prevention is not only more humane, but also more cost-effective. When governments prioritize early intervention and local care delivery, they reduce hospital overcrowding, minimize catastrophic out-of-pocket spending, and protect families from falling into poverty due to medical costs.

Financing Universal Health Coverage Through Local Resources

Achieving health care justice requires sustainable financing. Many low- and middle-income countries have historically relied on external assistance, but global aid dynamics are changing. National governments are increasingly expected to mobilize domestic resources and design systems that reflect their own priorities. Universal health coverage depends on pooling risk through insurance mechanisms and reducing direct payments at the point of care.

One underutilized opportunity lies in diaspora engagement. Redirecting even 1% of remittances toward national health insurance schemes could generate billions of dollars annually. At the same time, illicit financial flows continue to drain public resources. Africa alone loses an estimated $88 billion to $90 billion every year through illegal capital flight, funds that could otherwise strengthen hospitals, workforce training, and essential medicines. Addressing these losses is not only an economic issue but a moral one, as highlighted in global transparency and development discussions hosted by the United Nations (https://www.un.org).

Health financing reform also requires public trust. When citizens see tangible improvements in service quality and availability, they are more willing to contribute financially and support reforms. Justice, in this sense, becomes a shared social contract between governments and the people they serve.

Behavior, Culture, and the Future of Health Equity

Health systems do not operate in a vacuum. Behavior, culture, and social norms play a decisive role in whether services are used effectively. Many public health interventions focus heavily on awareness while overlooking motivation and social reinforcement. Behavioral science shows that people are more likely to adopt healthy practices when information is paired with trust, community support, and easy access to services.

Efforts to increase vaccination rates among adolescent girls illustrate this principle. Programs that combine digital communication, trusted local pharmacists, and family engagement have shown higher uptake of preventive services such as the HPV vaccine. Public health authorities, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, emphasize that reducing barriers and misinformation is essential to protecting future generations from preventable diseases (https://www.cdc.gov).

Personal experiences often reinforce the urgency of reform. When families are forced to travel long distances or leave their home countries for specialized treatment, the human cost of weak health systems becomes painfully clear. These realities underscore why King’s vision remains relevant today. Health care justice is not a distant ideal; it is a practical necessity for dignity, productivity, and social stability.

As the world reflects on leadership and responsibility, King’s enduring question remains central to the global health debate: what are we doing for others? Addressing health care inequality through primary care, fair financing, and behavior-informed solutions is one of the most powerful ways to answer that call and move closer to a future where justice truly includes health for all.