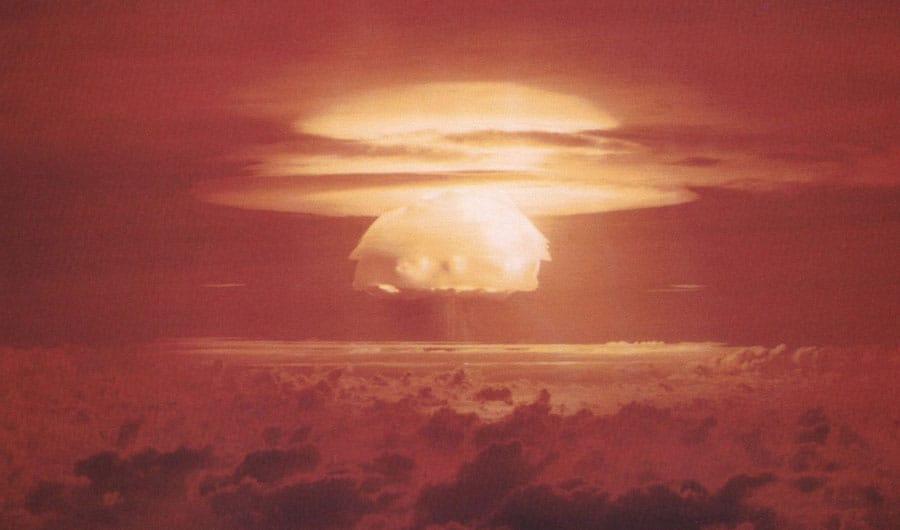

Eighty years after the detonation of the first nuclear weapon, the echoes of that moment still resonate—deep within our environment and even inside our bodies. Known as the “bomb spike“, the sudden and sharp rise in carbon-14 caused by mid-20th-century nuclear tests has provided scientists with a unique and enduring marker. The first nuclear explosion, the Trinity test, took place on 16 July 1945 in New Mexico. It released an 18.6-kiloton blast that not only reshaped military history but also altered the chemical composition of the planet’s atmosphere.

The explosion lofted radioactive particles into the sky, which then rained down over thousands of square miles. This test marked the dawn of the atomic age, followed by more than 500 above-ground detonations across the globe—primarily by the United States and the Soviet Union. These tests increased atmospheric carbon-14, a radioactive isotope of carbon, to nearly double natural levels. Unlike the immediate radioactive fallout, which posed clear dangers, the carbon-14 spike was not harmful. In fact, it became a scientific boon.

Unlocking Human Histories and Environmental Change

The carbon-14 from nuclear tests dispersed through every major carbon cycle on Earth. It entered plants, water, and animals, and through the food chain, found its way into human bodies. This created a time-stamped signature in our DNA, teeth, bones, and even the lenses of our eyes. Scientists quickly realized that they could use this marker to determine when specific cells were formed, helping to answer previously unsolvable questions in forensics, neuroscience, and environmental science.

One of the first practical uses of the bomb spike was in forensic science. When unidentified remains are found, scientists can now estimate a person’s birth or death year with surprising accuracy by analyzing the carbon-14 in teeth or bones. In some war crimes and genocide investigations, bomb spike dating has been instrumental in establishing timelines. It was even used to date a body found in a lake in Italy, confirming the year of death.

Meanwhile, neuroscientists have used the bomb spike to trace the formation of neurons in the human brain. Research has shown that some brain regions, like the hippocampus, continue to generate new neurons throughout adulthood. This discovery overturned the longstanding belief that adults could not grow new brain cells. Similarly, studies revealed that fat cells in the human body are regularly renewed, reshaping our understanding of metabolism and obesity.

The spike’s usefulness doesn’t end with biology. It is also etched into ice cores, sediments, corals, and even cave formations. This widespread presence has led geologists to consider it as a potential marker for the Anthropocene—a proposed new geological epoch defined by human impact. A group of scientists recommended Crawford Lake in Ontario, Canada as the site for the epoch’s formal marker. Though the designation has faced bureaucratic hurdles, it remains a symbol of humanity’s profound influence on the Earth.

A Radiocarbon Timestamp That Endures

Radiocarbon dating, the technique that measures the decay of carbon-14 over millennia, traditionally focused on ancient samples. But the bomb spike offers a new angle. Since the 1950s, carbon-14 levels in the atmosphere have steadily decreased, allowing scientists to date materials formed within the last 70 to 80 years—far more precisely than before. A tissue sample from someone born in 1955, for instance, will show higher carbon-14 than one from 1985, creating a kind of internal timestamp.

Beyond forensics and environmental records, the bomb spike has aided research into the provenance of food and wine, as well as wildlife tracking. Scientists can verify the vintage of a bottle of wine or determine whether an ivory tusk came from a poached elephant after the international ban. It also helps scientists date ancient sharks, some of which may live for centuries.

Despite its origin in nuclear catastrophe, the bomb spike has become one of the most valuable scientific tools of the modern age. Its unintended consequences have helped us unlock the secrets of our cells, our crimes, and our climate. Even as carbon-14 levels begin to normalize, the signature remains—etched into our biology and our environment, silently bearing witness to a pivotal moment in human history.