There are many reasons to learn a new language: love, work, personal interest in a culture or its people. But beyond these motivations, scientific research shows that language learning also benefits overall brain health—it essentially works like mental exercise. But what actually happens in the brain when we acquire a new language?

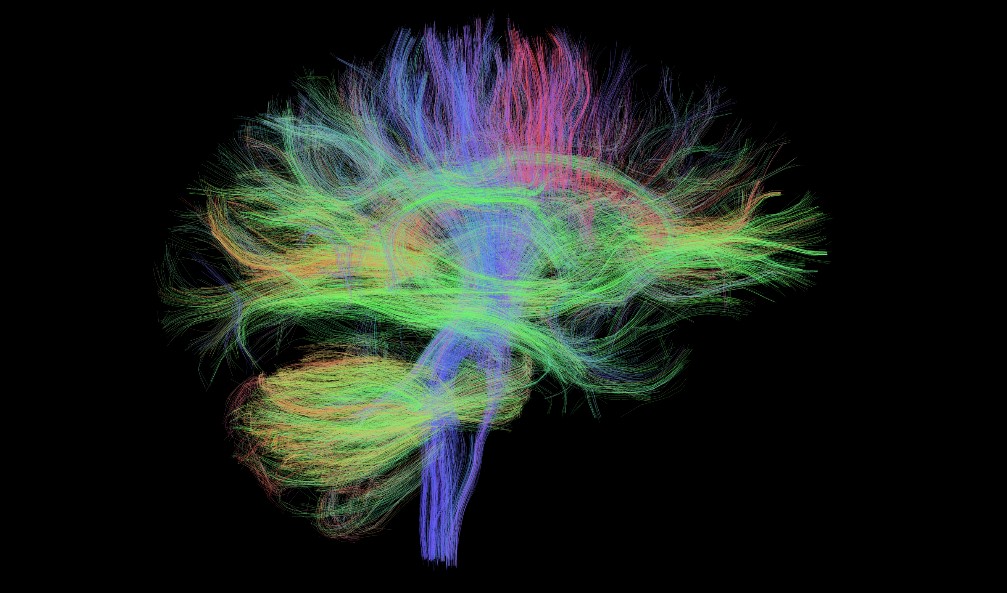

The Brain’s Language Areas

Producing language requires many different parts of the brain. According to Arturo Hernández, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Diego, two main neural circuits are involved: one responsible for perceiving and producing sounds, and another for selecting which sounds to use.

“These circuits get reconfigured as we learn and switch languages. It’s about mapping sounds and deciding which language to operate in,” Hernández explains. In general, for any language, we rely on sensory regions such as the auditory cortex to process the sounds of speech.

Additionally, the brain’s extensive motor networks are essential for coordinating the muscles involved in speaking—those controlling the tongue, lips, and vocal cords. But learning a new language also prompts changes in the brain’s higher-order processing areas.

Physical Changes in the Brain

A 2024 German study measured brain activity in Syrian refugees before, during, and after learning German. The researchers found that participants’ brains physically restructured as they learned the language. This process, known as neuroplasticity, reflects the brain’s ability to reorganize its neural pathways in response to learning.

“Structurally, [language learning] increases the volume of grey matter in areas related to language processing and executive function,” says Jennifer Wittmeyer, a cognitive neuroscientist at Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania.

These structural changes also affect brain function by altering the way neurons communicate. This neural plasticity improves the ability to recall words, recognize new sounds, and refine pronunciation through better control of mouth muscles.

The Advantage of Learning Languages as a Child

Studies show that the brain uses the same networks for all languages, but it responds differently to the mother tongue. One study found decreased brain activity in language networks when participants listened to their native language.

Researchers suggest that the first language is processed more efficiently, with minimal effort. It’s also well established that young children find it significantly easier to learn new languages than adults.

Children’s brains are still developing and are more adaptable to neuroplastic changes. Unlike adults, they don’t need to translate from their native language, which makes it easier to absorb sounds, grammar, and vocabulary.

“At an early age, there’s less rigidity in the brain. Adult brains are already structured around their first language, so a second language must fit into existing knowledge, instead of developing independently, since it relies on pre-established neural networks,” Hernández explains.

Does Learning a Language Make You Smarter?

Some research suggests that multilingualism enhances cognitive functions like memory and problem-solving. But does this mean polyglots are smarter? It’s a difficult question, and probably not, says Hernández.

It remains unclear whether people who know more words have greater cognitive reserves or simply store more vocabulary in their memory banks—something that doesn’t directly equate to intelligence.

To truly test if multilingual people are more intelligent, scientists would need to “find a task that’s not related to language,” Hernández adds. So far, no strong evidence shows that multilingual individuals perform better on non-language-related tasks.

Researchers also point out that cognitive changes seen in multilinguals may be influenced by other factors, such as education or the environment in which they were raised. There are simply too many variables involved in cognitive ability to isolate language learning as the sole contributor, experts say.